White Matter Hyperintensities Linked to Alzheimer’s Disease

A new study adds to a growing body of evidence pointing to small-vessel cerebrovascular disease as an important contributor to Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

A new study adds to a growing body of evidence pointing to small-vessel cerebrovascular disease as an important contributor to Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

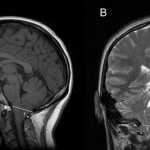

The study shows that increased total white matter hyperintensities (WMHs) as seen on MRI independently predicted AD diagnosis, as did the brain amyloid tracer Pittsburgh compound B (PIB) measured by positron emission tomography (PET).

This finding suggests that although amyloidosis is necessary for a diagnosis of AD, it may not be sufficient to cause dementia and that WMH may represent another important pathogenetic factor that contributes to dementia.

“This study, along with a whole line of research that is coming out right now, is clearly highlighting the importance of vascular disease in Alzheimer’s disease,” said author Adam M. Brickman, PhD, assistant professor of neuropsychology at Columbia University, New York.

“In the past, we didn’t conceptualize AD as having a vascular component at all — we typically thought of it only as plaques and tangles — but now we’re showing, and other groups are showing, that these vascular lesions may be as important.”

The study was published online February 18 in JAMA Neurology.

ADNI Data

The researchers used data obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), which was launched in 2003 by the National Institute on Aging, the Food and Drug Administration, pharmaceutical companies, and various other groups.

The goal of ADNI is to test whether serial MRI, PET, other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessments can be combined to measure the progression of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD.

From the ADNI database, the researchers downloaded data from 21 normal controls, 59 patients with MCI, and 20 patients with clinically defined AD. The 3 groups were similar in age, sex distribution, and modified Hachinski Ischemic Scale score.

The investigators also downloaded data from carbon 11–labeled PIB-PET scans. And they derived total WMH volumes for the participants from MRI.

Twenty-eight participants (68%) were classified as PIB positive, of whom 17 met clinical criteria for AD, and 13 participants were classified as PIB negative, of whom 3 met criteria for AD.

The mean total WMH volume was 5.71 cm3. Total WMH volume did not differ between PIB-positive and PIB-negative participants. However, there was a significant negative association between cortical PIB-uptake values and total WMH volume among all participants, including those with MCI.

The analysis demonstrated that higher WMH volume (P = .02) and PIB positivity (P = .049) were each independently associated with AD diagnosis. Age was not associated with the diagnosis.

As well, the analysis showed that patients with AD had greater WMH burden than normal controls who also were PIB positive.

WMH volume discriminated between persons with clinical AD and normal controls. Setting a cutoff at 1.25 cm3, total WMH volume yielded a sensitivity of AD classification of 83% and a specificity of 64%.

Of 59 participants with MCI, who were followed for about 2.5 years, 37% converted to AD. When comparing these patients with MCI according to their PIB positivity and high or low WMH volume, the researchers found that both of these factors were significant predictors of future conversion to AD.

Researchers don’t yet know how amyloid and WMHs are connected. “We showed a modest correlation between PIB positivity and WMH volume, suggesting that if you have a lot of WMHs, you also have a lot of amyloid in your brain, but that’s certainly not a definitive indication that they are mechanistically related,” said Dr. Brickman.

To get a better handle on the connection, the researchers are studying the pathologic basis of WMHs by investigating postmortem tissue with MRI and histologic techniques. “That might help us understand if the pathological basis of the WMHs is related to, [is] co-localized, or co-occurs in the same regions as the amyloid we see in AD,” said Dr. Brickman.

Tip of the Iceberg

But current MRI technology may not be sensitive enough to pick up all the pathologic features associated with WMH. “What we could be dealing with here is just sort of a tip-of-the-iceberg phenomenon,” said Dr. Brickman. “Everyone who has WMH could have these pathological features in their white matter, but we may not be detecting everyone who has those features with our current technology.”

In the future, though, MRI showing WMH could eventually become an important tool to help determine the presence of AD. “We have a syndrome of AD that looks like cognitive impairment with functional disability and I think there are various pathological features that contribute to that syndrome,” said Dr. Brickman. “In one person, it might be more of an amyloid and tangles story, and in another person, it might be more amyloid and vascular disease.”

Dr. Brickman stressed that AD is “a really heterogenous disease” and perhaps “not as simple as some of the theoretical models about the pathogenesis make it seem to be.”

In light of these results, it might become increasingly important to control risk factors for WMHs, said Dr. Brickman. These risk factors are essentially the same as those for stroke and include hypertension, diabetes, obesity, heart disease, and smoking.

“We know that all these risk factors, at least in the epidemiological literature, have been associated with the risk for AD, and here we’re showing that perhaps the mechanism through which they confer risk has to do with these small lesions we see on MRI scans,” said Dr. Brickman, adding that preventing these lesions is likely a “lifelong process.”

It’s unclear, though, whether controlling vascular risk factors and preventing the accumulation of WMHs would prevent AD, he said. “But I think there is a growing amount of evidence to suggest that control of vascular factors can at least reduce the risk, maybe delay the onset, and perhaps mitigate the symptoms of the disease itself.”

Open Area of Research

In an accompanying editorial, Karen M. Rodrigue, PhD, School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences, University of Texas at Dallas, observed that the contribution of vascular pathology to AD is an important and “open” area of current research.

The results of this study, said Dr. Rodrigue, indicate that among people with elevated brain amyloid levels, the WMH burden can discriminate between those with clinical AD and those who are cognitively normal.

“Additionally, both amyloid and WMH status combined to best predict who would convert to AD among those with MCI,” she writes.

Importantly, she pointed out that the study suggests that information about a patient’s WMH may help identify those who are at most risk for conversion to AD. “These findings have important clinical implications in light of the observation that 20% to 30% of cognitive healthy older adults show elevated amyloid levels.”

For a list of study sponsors, see the original article. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

JAMA Neurol. Published online February 18, 2013. Abstract Editorial